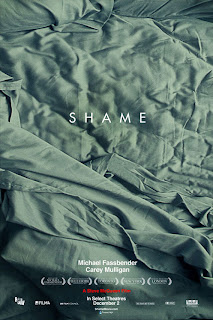

Shame (2011, Steve McQueen) is irreducible. It is about a young marketing professional who's a sex addict (Micheal Fassbender) and his suicidal sister (Carey Mulligan), set in New York. By the end of the film, nothing changes.

I'm split between two ways to read this movie. My first response was positive. Knowing the premise beforehand (Brandon's a sex addict), every shot rang completely true to his symptom. When I first saw the opening shot of Brandon catatonically staring at the ceiling, I projected that he wakes up with one thing on his mind and nothing else--the look of a junkie. And I thought, "brilliant, wow, that's exactly what it's like." I also thought the music, pacing and composition were refined, and that the film did so much in such an understated way.

But after reflection, I was not so sure. Hunger (2008, Steve McQueen) is a bona fide masterpiece about an historical figure who sacrifices his self through starvation to make a political statement in a humanitarian way. Shame's Brandon is the opposite: he indulges his sexual appetite and cares for nothing and nobody. And as a character, what the hell do I care about some rich upper-East side yuppie who gets laid as much as humanly possible? Seriously? Sympathy? For that? I realized, with a different filmmaking approach, I would not be empathizing with this guy's misery, I'd be appalled by the audacity someone had to have to think anyone actually cares about this character's conquests--it might even be nothing more than high dollar softcore.

In conclusion, Steve McQueen is a brilliant visual artist. In the film's beginning, there is an edit that is joined by a shot of Brandon jacking off in the shower that goes soft (blurry) on an MCU of him, which is followed by a match cut of a soft focus MCU of Brandon on the subway.

Also, there's a now signature McQueen overhead shot, composed with perfect symmetry: Brandon taking a bathroom break during work and what he does in the stall.

Then there's the first POV of Marianne in Brandon's office: she appears naked from the shoulders up (even though in the diegetic world she's clothed), and the frame is disturbed--what are we looking at? Her shoulders? Her lips? One eye?

The other two big sequences are: the tracking dolly shot of Brandon running out in the city at night, which follows him as he falls off into black, then catches him sporadically as he approaches overhead sources (also similar to the technique employed for he and Marianne's first walk and, maybe, inspired by the EXT. night shots in Army of Shadows (1969, Jean-Pierre Melville)); and the six minute two shot of he and Sissy (Mulligan) talking on the couch. I probably don't need to point this out, but six minutes is an exceptionally long duration for a shot, especially in the modern cinematic climate of today. (And Steve McQueen's most famous shot from Hunger is an uninterrupted seventeen minute take of two guys talking that is unlikely to be rivaled anytime soon.)

Like I said, it's impressive how every shot works by staying with Brandon or Sissy and omits dialogue for moments of silence and stillness, but preserves focus and remains truthful to their story.

--Dregs

Found Laying Around the Shop

▼

Thursday, April 26, 2012

Tuesday, April 24, 2012

Driven

My favorite films are dark and feminine. Recently, for feminine, there's:

Violet (Greta Gerwig) is a decoy who initially appears to be Charlotte (Kate Beckinsale) from The Last Days of Disco, but reveals truly unexpected character turns that layer onto her initial appearance--vacuum headed eccentric who seems to aim low, but with an air of superiority, claims virtuosity and altruism (the variant is that Violet is as naïve as Charlotte is cynical). And this is her vehicle to say some of the most insanely offbeat lines I never saw coming. The tone is set in the opening, when Violet scorns some male coed passersby because of their "acrid odor." The score under moments like this is audaciously prim, which signals the film's knowingness of its own satirical edge.

I've spoken a lot lately about how films only convey sight and sound, and that the other senses like smell, taste and touch must be evoked through other means. It's unimportant at this point, but smell seemed a big part of Hunger (2008, Steve McQueen) for me because I felt like he created a constant smellscape of putrid stench. Violet's character evokes smell in several ways. She even goes into a funny speech about how the smell of one's environment has a direct bearing on their state of being.

Violet also speaks with proper formality and impeccable diction. And it never ceases to be hilarious and charming. (To regretfully digress yet again, Veda from Mildred Pierce has the most brilliant dialogue because it's also period; but, her prim and proper orations are daggers and one of the strongest parts of that film.)

This film constantly reminded me that I was in new territory, which I mean in a good way. It cannot be taken seriously, but it touches serious emotions and ideas. And Whit Stillman is a clever craftsman, in an elegantly minimalist way.

Violet has three close friends who support her adequately. Lily (Analeigh Tipton) becomes very prominent and is intriguing to look at--she has a distinguishing scar on her cheek that almost looks decorative. But of course, Gerwig is the core of Damsels in Distress, and her turn as Violet will be what lasts with audiences.

--Dregs

- The Last Days of Disco (1998, Whit Stillman) glamorous, chic, and witty.

- Dancer in the Dark (2000, Lars von Trier) dark musical.

- Amélie (2001, Jean-Pierre Jeunet) so saccharine and girly, although light.

- Mulholland Dr. (2001, David Lynch) scary Hollywood dream/nightmare.

- Palindromes (2006, Todd Solondz) dark adolescent satire.

- Marie Antoinette (2006, Sofia Coppola) pink period/pop art.

- Volver (2006, Pedro Almodóvar) Classic Hollywood-style domestic melodrama.

- Black Swan (2010, Darren Aronofsky) scary ballet dream/nightmare.

- Mildred Pierce (2011, Todd Haynes) the final word in the genre, period.

Violet (Greta Gerwig) is a decoy who initially appears to be Charlotte (Kate Beckinsale) from The Last Days of Disco, but reveals truly unexpected character turns that layer onto her initial appearance--vacuum headed eccentric who seems to aim low, but with an air of superiority, claims virtuosity and altruism (the variant is that Violet is as naïve as Charlotte is cynical). And this is her vehicle to say some of the most insanely offbeat lines I never saw coming. The tone is set in the opening, when Violet scorns some male coed passersby because of their "acrid odor." The score under moments like this is audaciously prim, which signals the film's knowingness of its own satirical edge.

I've spoken a lot lately about how films only convey sight and sound, and that the other senses like smell, taste and touch must be evoked through other means. It's unimportant at this point, but smell seemed a big part of Hunger (2008, Steve McQueen) for me because I felt like he created a constant smellscape of putrid stench. Violet's character evokes smell in several ways. She even goes into a funny speech about how the smell of one's environment has a direct bearing on their state of being.

Violet also speaks with proper formality and impeccable diction. And it never ceases to be hilarious and charming. (To regretfully digress yet again, Veda from Mildred Pierce has the most brilliant dialogue because it's also period; but, her prim and proper orations are daggers and one of the strongest parts of that film.)

This film constantly reminded me that I was in new territory, which I mean in a good way. It cannot be taken seriously, but it touches serious emotions and ideas. And Whit Stillman is a clever craftsman, in an elegantly minimalist way.

Violet has three close friends who support her adequately. Lily (Analeigh Tipton) becomes very prominent and is intriguing to look at--she has a distinguishing scar on her cheek that almost looks decorative. But of course, Gerwig is the core of Damsels in Distress, and her turn as Violet will be what lasts with audiences.

--Dregs

Thursday, April 19, 2012

Torque

Since I was fourteen, I've known I want to write and direct my own movies. There's nothing I've thought about more or invested as much of myself into the pursuit of. There are quite a few ideas I've had that involve drastically reinventing the cinematic language. Every once in a while, I'm surprised to see another filmmaker, before anyone else, achieving something I'd only dreamed of.

Case in point: the notion I've fancied for some time now of someone making a feature length motion picture that did everything a Britney Spears music video or Chanel perfume commercial does in a minute, only for the ninety minute duration of a movie.

To assess this chronology thus far:

...mostly.

Scott Pilgrim vs. the World brought many of the motifs Wright had pioneered in the watershed Spaced TV series, which aired on Britain's Channel 4 from 1999-2001. During Spaced, Wright liberally parodied various Hollywood genres, in his Tarantino-like, fanboy way. The key to what makes Scott Pilgrim vs. the World so unique is its frenetic, hyper-self-aware style of visual onslaught, with constant pop-ups of text providing up-to-the-minute exposition during, and often before its context becomes apparent. That shit is not from video games; Wright was tapping into the aesthetics of MTV music videos.

Detention (2011, Joseph Kahn) finally delivered what I'd been awaiting: a ninety minute feature that constantly sells itself as a music video--it's like eating a huge, eleven-course meal where all of the entrées are cotton candy, pixy stix and cocaine, with only Jolt cola to wash it all down.

The narrative is unlike anything I've ever seen, including Scott Pilgrim vs. the World. Grizzly Lake High, as a location, contains the milieu of this cast of characters, although there are quite a few times when the story follows some into intergalactic galaxies, and others who are cavorting through the space-time continuum.

I can't help myself from giving away a little of the goodies (major spoilers in this and the next ¶). The film begins with a Ferris Beuller style direct address (character breaking fourth wall), nodding to Clueless's (1995, Amy Heckerling) Cher along the way, as Taylor Fisher (Alison Woods) tells us how to follow her "Guide to Not Being a Total Reject." The on-screen text is eponymous and resembles Tarantino's style of chapter breaks, especially in the style he began using on Kill: Bill vol. 1 (2003, Quentin Tarantino), which he obviously got from Vivre sa vie: film en douze tableux (1962, Jean-Luc Godard). As old as I am, I seemed to get most of the dialogue and pop culture references during this sequence, and actually felt like I think I got more out of this movie than teenagers will, in this regard.

And, the ensemble is made up of students of Grizzly Lake. The killerest part is that each of the stereotypically John Hughesian characters are living in their own hyper-aware, emotionally overwhelming teen dramas that respectively get played out as isolated movies, each apologetically embodying a different genre. Riley Jones (Shanley Caswell) lives in TV's My So-Called Life (1994); Ione (Spencer Locke) is in a Freaky Friday (2003, Mark Waters) meets Back to the Future (1985, Robert Zemeckis) plot; and Billy (Parker Bagley) is living The Fly (1986, David Cronenberg).

But this still doesn't quite communicate what exactly you get with Detention. Each vignette is titled, as its own chapter, but by the end you realize they're all insanely interlocked and build layers on top of each other that all work. Well, except the tilt-shift heavy "The Mysterious Tale of the Time Travelling Bear."

(End spoilers)

Kahn's music video aesthetic begins with his fancy for lens flares. I believe this was invented on Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977, Steven Spielberg), where Vilmos Zsigmond intentionally utilized the blue streaks of light that play out in anamorphic lenses when you aim uncorrected HMIs at it. But Kahn realized it looks cooler to key light Britney Spears with this technique (see the music video "Stronger"), instead of Spielberg using it to just hide what were maybe UFOs. Kahn also loves to push in on characters, a lot (I heard some kid saying that all Fincher's style is is pushing in--I kind of disagree). But, Kahn also uses "geometric editing" and vectors to put his puzzle together.

And the color temperature in Detention is typically a blueish frontal and overhead diffused source mixed with golden backlights and sidelights to mimic sunlight--which is actually very distinguished, fresh and works.

So, Kahn's narrative, his music video aesthetic and a ton of awesome pop songs and pop culture references (I mean really ambitious pop culture references, not Diablo Cody one-liners) make this film a new personal favorite of mine. The Ione character is so fun and cute--she's like if Taylor Momsen tried to be "Hit Me Baby One More Time" era Britney. Detention's an oasis in the desert of dull narrative filmmaking and I wish I could watch it again soon.

--Dregs

Case in point: the notion I've fancied for some time now of someone making a feature length motion picture that did everything a Britney Spears music video or Chanel perfume commercial does in a minute, only for the ninety minute duration of a movie.

To assess this chronology thus far:

- Go (1999, Doug Liman)

- Requiem for a Dream (2000, Darren Aronofsky)

- Spun (2002, Jonas Åkerlund)

- Domino (2005, Tony Scott)

- Speed Racer (2008, Andy Wachowski and Lana Wachowski)

- Scott Pilgrim vs. the World (2010, Edgar Wright)

...mostly.

Scott Pilgrim vs. the World brought many of the motifs Wright had pioneered in the watershed Spaced TV series, which aired on Britain's Channel 4 from 1999-2001. During Spaced, Wright liberally parodied various Hollywood genres, in his Tarantino-like, fanboy way. The key to what makes Scott Pilgrim vs. the World so unique is its frenetic, hyper-self-aware style of visual onslaught, with constant pop-ups of text providing up-to-the-minute exposition during, and often before its context becomes apparent. That shit is not from video games; Wright was tapping into the aesthetics of MTV music videos.

Detention (2011, Joseph Kahn) finally delivered what I'd been awaiting: a ninety minute feature that constantly sells itself as a music video--it's like eating a huge, eleven-course meal where all of the entrées are cotton candy, pixy stix and cocaine, with only Jolt cola to wash it all down.

The narrative is unlike anything I've ever seen, including Scott Pilgrim vs. the World. Grizzly Lake High, as a location, contains the milieu of this cast of characters, although there are quite a few times when the story follows some into intergalactic galaxies, and others who are cavorting through the space-time continuum.

I can't help myself from giving away a little of the goodies (major spoilers in this and the next ¶). The film begins with a Ferris Beuller style direct address (character breaking fourth wall), nodding to Clueless's (1995, Amy Heckerling) Cher along the way, as Taylor Fisher (Alison Woods) tells us how to follow her "Guide to Not Being a Total Reject." The on-screen text is eponymous and resembles Tarantino's style of chapter breaks, especially in the style he began using on Kill: Bill vol. 1 (2003, Quentin Tarantino), which he obviously got from Vivre sa vie: film en douze tableux (1962, Jean-Luc Godard). As old as I am, I seemed to get most of the dialogue and pop culture references during this sequence, and actually felt like I think I got more out of this movie than teenagers will, in this regard.

And, the ensemble is made up of students of Grizzly Lake. The killerest part is that each of the stereotypically John Hughesian characters are living in their own hyper-aware, emotionally overwhelming teen dramas that respectively get played out as isolated movies, each apologetically embodying a different genre. Riley Jones (Shanley Caswell) lives in TV's My So-Called Life (1994); Ione (Spencer Locke) is in a Freaky Friday (2003, Mark Waters) meets Back to the Future (1985, Robert Zemeckis) plot; and Billy (Parker Bagley) is living The Fly (1986, David Cronenberg).

But this still doesn't quite communicate what exactly you get with Detention. Each vignette is titled, as its own chapter, but by the end you realize they're all insanely interlocked and build layers on top of each other that all work. Well, except the tilt-shift heavy "The Mysterious Tale of the Time Travelling Bear."

(End spoilers)

Kahn's music video aesthetic begins with his fancy for lens flares. I believe this was invented on Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977, Steven Spielberg), where Vilmos Zsigmond intentionally utilized the blue streaks of light that play out in anamorphic lenses when you aim uncorrected HMIs at it. But Kahn realized it looks cooler to key light Britney Spears with this technique (see the music video "Stronger"), instead of Spielberg using it to just hide what were maybe UFOs. Kahn also loves to push in on characters, a lot (I heard some kid saying that all Fincher's style is is pushing in--I kind of disagree). But, Kahn also uses "geometric editing" and vectors to put his puzzle together.

And the color temperature in Detention is typically a blueish frontal and overhead diffused source mixed with golden backlights and sidelights to mimic sunlight--which is actually very distinguished, fresh and works.

So, Kahn's narrative, his music video aesthetic and a ton of awesome pop songs and pop culture references (I mean really ambitious pop culture references, not Diablo Cody one-liners) make this film a new personal favorite of mine. The Ione character is so fun and cute--she's like if Taylor Momsen tried to be "Hit Me Baby One More Time" era Britney. Detention's an oasis in the desert of dull narrative filmmaking and I wish I could watch it again soon.

--Dregs

Tuesday, April 17, 2012

Biker Boyz

The duality of man theme expressed in Full Metal Jacket (1987, Stanley Kubrick) shows how man’s id can be tapped to create a killing machine; and, say, one that risks exterminating his ego and superego as a result (i.e. Pyle and Animal Mother).

For this reason, Full Metal Jacket is one of the 2 most important films I’ve seen, thematically. And for this same reason, I find it the one movie that best suited Kubrick’s talent and vision. And, that vision is cynical, satirical, and dystopian, to say the least.

The other most important film, thematically, for me, is Au hasard Balthazar (1966, Robert Bresson). Au hasard Balthazar has been my favorite movie for years. It’s the one movie I actually love.

Instead of showing the duality of man, Bresson links man to animal through their souls. He shows that man is not a paradox, but a spirit, just as all living creatures are. But, Bresson also believes all of our destinies to be martyrdom.

Le gamin au vèlo (2011, Jean-Pierre Dardenne and Luc Dardenne) is very much concerned with the same aesthetic reverence and milieu of Bresson. Its central protagonist, Cyril, has a desperate hunger in his spirit to understand his purpose in life. He strives to decide if he’s a boy or an animal. And this juxtaposition is central, for the core of the film is this dilemma.

The narrative is a diptych in the sense that first, Cyril fights to understand what’s up with his dad, then the second half of the film arises after what Cyril does after he finds out.

The brilliance of Le gamin au vèlo’s focus arises from the blurring of the lines between boy and animal; because, all Cyril needs to be able to live as a boy is a parent, yet the film expands the elasticity of that connotation. In effect, what this establishes is the perspective that shows how the exact same thing is true of animals—or, as Au hasard Balthazar hypothesizes, kindness nurtures and is necessary for a spirit to exist and cruelty kills it, for humans and animals alike.

With the same ferocity as Alan Clarke’s characters like Gary Oldman in The Firm (1989, Alan Clarke) or the two adolescents in Christine (1987, Clarke), Cyril has a primal inertia. He sprints, attacks, bites, scales walls, climbs trees, and it’s easy to anticipate what he’s like once he gets on his bike—it becomes a Maverickian extension of his need for speed, or, more accurately, stress release and an escape.

The typical Dardennes camera style is maintained: handheld and documentary style. Yet, they also spend quite a bit of time on fluid

tracking shots of Cyril.

The color scheme calls attention to itself. Cyril always wears red, except for one shot. In color theory, primary red’s complimentary hue is primary cyan. In Le gamin au vèlo, Cyril appears in the first shot wearing a primary cyan tee under his zip-up primary red jacket. I actually believe right now that cyan represents Cyril’s spirit. (Other instances where primary cyan occurs are: the nighttime interiors when Cyril sleeps; and to a lesser extent, the accents in Cyril’s bedroom on the estate, and the clothes worn by other boys he encounters on the streets—notice which men wear black.) Finally, there is a crucial moment in the third act wear Cyril wears a primary cyan tee under a denim jacket, with no red—the only time in the film—and, during this scene, the one chance Cyril felt to be worthy of actually living as a boy with a spirit, it just so happens that life is a little more complicated and I’ll leave it at that. (You know it wouldn’t be a Dardenne brothers movie without that awesome "this can’t last" kind of dénouement, like Sirk at his best.)

The Dardennes are still the masters of minimalism when it comes to music. In Le gamin au vèlo, their sixth narrative feature, they use non-diegetic music for the first time—but it’s hardly anything resembling an actual score. The Beethoven cues really feel like the way Bresson portioned out the Mozart in certain moments during Un condamné à mort s' est èchappè ou Le vent souffle où il veut (1956, Bresson).

Basically, I identify most strongly with Cyril’s wild side; especially considering that pretty much all he’s after, underneath it all in the end, is someone to love him. That, to me, is a beautiful paradox: one’s wild animal nature ferociously fighting to find peace and love.

And the fact that movies this simple can still be made still remains a feat to me. I think its a wonder to be able to watch stories play out that can feel this honest and modern, with such lack of fuss over spectacle or high production values in the serivce of genre conventions.

--Dregs