Found Laying Around the Shop

Monday, June 24, 2013

When You Hear the Words Foreign Film, Think of France

Sometime around the early to mid aughts I had repeatedly skimmed the title Beau travail (1999, Claire Denis) in print articles found in the New York Film Society at Lincoln Center's monthly "Film Comment," often in best of lists. I'd also been hounding David Thomson's The New Biographical Dictionary of Film and come across his monograph of Claire Denis--he specifically refers to her biggest fans being "the 'Film Comment' critics." So, I finally gave Beau travail a chance around 2009.

Claire Denis is probably my most recent discovery that has allowed me to find that elusive scent I hunt down so desperately--that of creative aesthetic brilliance. (Actually, Bruno Dumont is the most recent, to be accurate.) Beau travail won me over firstly with its short running time, splendid Benjamin Britten score, and insurmountably calculated final shot.

I love Beau travail as a foreign film. It's foreign in many senses of the word, especially for me. Denis uses tiny details to establish the Djibouti location in ways that evoke its people, markets, landscapes, transportation systems, and merciless barren deserts along with marvelously azure coastal planes. When I watch this, I always appreciate the quality of being transported to Africa for an hour and a half--and I've never been to Africa, but it strikes me as the most foreign of continents because I have the hardest time imagining what it would actually be like to visit.

The iconic French veteran actor Denis Lavant (he's got a mug like a French Dafoe) stars as Sgt. Galoup, an inwardly-turmoiled French Foreign Legionnaire who struggles with his jealousy over the new thin recruit Sentain. So the foreigner stacking piles up here: Galoup is a Frenchman in Africa, appears to be either a closeted homosexual or conflicted similarly with a dark impulse that arises out of his jealousy over Sentain, and all of this was filmed by a 43 year old French woman who AD'd for Wim Wenders and Jim Jarmusch throughout the 80s (Don't tell me you can't think of Wenders' Paris, Texas (1984) or Jarumusch's Stranger Than Paradise (1984), or Down by Law (1986) as having a similarly foreign protagonist in a foreign place, typically encountering other foreigners).

The Djibouti discotech scenes are easily some of the finest craftsmanship Denis has arranged, infusing the bleak desert locale with lively colors, seductively corporal gyrations, darkness and energy. This counterpoint evokes part of the mysterious inner life of Galoup.

It was Godard who famously said that, "a film needs to have a beginning, a middle, and an end. But, not necessarily in that order." Beau travail's famous final shot has been reported numerous times to have been found at another point in the script initially; only in post did Denis realize where she wanted to put it. But, this holds as a vital example to Godard's original intent.

This is the rhythm of the night.

Galoup's queer demeanor is a locked door. Perhaps we will never really know him. However, it is clear that he lives for the corps--the Foreign Legion, his body, their bodies, Sentain's body, and even Rahel's (Galoup's African mistress) body. But, the final shot nearly guarantees to us that there is something locked up behind that door that is bursting forth to get out--the subjective responsibility of the audience is to spend a moment trying to think about it.

Last night getting to watch this in 35mm (the print was a little scratchy) was a welcome and refreshing oasis in my week of watching big budget effects movies.

--Dregs

Saturday, June 22, 2013

Paramount's Plagued Production

But, for the most part, the movie feels like it keeps striking the same note again, and eventually becomes a little monotonous.

End SPOILERS.

When I first began writing for Reviewiera, I had envisioned the goal of subjectively writing film criticism (as opposed to movie reviews) and writing predominantly from a first person perspective that would allow any digressions as long as I felt they were pertinent.

But, sometimes I've found myself slacking lately. And unfortunately, the result is shoddy tidbits of criticism. At least when I say something, I've tried to back it up.

So, this week I was working on a Chevy Silverado commercial that was directed and shot by one of my artistic heroes, cinematographer Robert Richardson. I picked him up from the airport 2 weeks ago and immediately gushed about how I'd been indoctrinated into personal/subjective filmmaking when I was 13 because of Natural Born Killers (1994, Oliver Stone). He was very cool and brought me along to have dinner at uchi (probably the hottest sushi restaurant in Austin--I can't believe I just said that) with he and his producer and production designer.

And nearly 20 years after being dragged out of Natural Born Killers 10 minutes into it by my disapproving parents (in their defense, maybe that isn't a movie a 13 year old should watch), my influences have remained uncannily consistent.

Richardson shot every Oliver Stone movie from Salvador (1986, Stone) to U Turn (1997, Stone), winning an Oscar for JFK (1991, Stone); he also shot Casino (1995, Martin Scorsese), which I always preferred to Goodfellas (1990, Scorsese) and when I was 14 I knew that the cinematography was stellar--he was the only D.P. I could identify by his style (particularly the blown out table tops and harsh source lighting), before reteaming with Scorsese for Bringing Out the Dead (1999, Scorsese), winnning his second Oscar for The Aviator (2004, Scorsese), Shutter Island (2010, Scorsese) and the film that earned him his third Oscar, Hugo (2012, Scorsese); and Bob's been Quentin Tarantino's D.P. since Kill Bill (2003/4, Tarantino).

I didn't see JFK until I was 24, but I fell in love with dude's style all over again. This was the same time I'd been punch drunk over Kill Bill.

If I didn't work with Bob this week I wouldn't have known that he shot World War Z, or that he took his name off of the movie because Paramount insisted on releasing the movie in 3D, despite the fact that the film was shot in 2D without 3D cameras. Richardson won an Academy Award for Best Cinematography for the 3D Hugo and knows what it takes to make a 3D movie right. Anyway, on the Chevy commercial I also got to meet Bob's 1st AC, Gregor Tavenner (whose credit is still on IMDb and in the movie), his Key Grip, Chris Centrella (whose credit is still in World War Z, but not on IMDb?), and Gaffer, Ian Kincaid (whose credit, like Richardson's, has been removed from IMDb and the finished film).

And earlier this week, after I'd spent an hour or so talking with Ian, he told me that Tarantino says, "Friends go see friends' movies on opening day," and that he always mails Tarantino a ticket stub to prove this every time he releases a new movie.

Basically I said all that to say normally I wouldn't have been inclined to go see World War Z, but I did it for Bob.

I see every Michael Bay movie in the theater, because since T2, I feel like he's inherited its legacy in a way, and dare I say, the Transformers films are the closest thing to T2 I've found for my tastes. (Okay, I'm also a little biased because I worked on Transformers 4 last week.) But I don't go for The Matrix films, the Star Wars prequels, J. J. Abrams, or Spielberg (although I do really like Mission: Impossible III (2006, J. J. Abrams), Spider-Man 3 (2007, Sam Raimi) and The Adventures of Tintin (2011, Steven Spielberg)). I've also never liked Peter Jackson's films because I don't like any wizards and faries films ever, but also because I feel, much like with Baz Luhrmann, that the spectacle is bloated and not edgy enough. But District 9 (2009, Neill Blomkamp) was stellar, even though I have yet to come fully on board--I can't wait to hear what Fat thought of Elysium (2013, Blomkamp).

So yeah, World War Z is a little flat and it suffers from the PG-13 curse of knowing Gerry (Pitt) and his family will be safe and he will be the hero who saves the world, to be fair. But it's got spectacle, and Bob's cinematography is amazing.

--Dregs

Tuesday, June 18, 2013

BEARDS NOT WORDS: (OR) Bostwick Redux

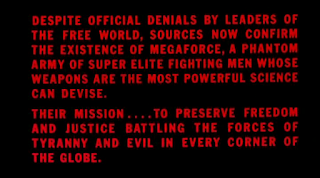

Tight bro @todf just put up the screen you see below, some introductionalizing textery from inexplicably talked-a-lot-about-by-us-on-Reviewiera film from 1982 and overall life model MegaForce. The film is, as the textery suggests, a thing of joy, inspiration, and rocket-powered beards motorcycles. (I will be suggesting to IMDB.com that "a thing of joy, inspiration and rocket-powered beards motorcycles" replace the description of the film currently available:

Story about a rapid deployment defense unit that is called into action whenever freedom is threatened.Though I am very excited about any IMDB movie description beginning "Story about". Wouldn't want to mistake anything for a documentary or non-narrative exercise!)

So I thought it would be fun to take a quick look back at a thing we return to as a dog returns to its vomit. Enjoy!

- Bostwick—Probably the single least explicable entry in the archives. Plucked bloody from the heart of conversation between Tinzeroes & Fat, this one is the most MegaForce moment in the history of Reviewiera.

- Red-Hot Flower of Hysteria—Offhand mention of MegaForce in Tinzeroes' magnum opus on SF zine Cheap Truth

- serpent-skinned—Offhand mention of MegaForce in a long ode to a mediocre childhood and the horror movies thereof

- Quick Look at the Cover

It's no Buckaroo Banzai, but as a relic of a simpler time, it will do. There is little wrong with a reminder that a more or less successful premise for a more or less successful film used to be "let's go tearassing around the desert on some dirt bikes and add laser effects later".

—Fat, under a fluttery banner reading DEEDS NOT WORDS

Thursday, June 13, 2013

The Fantastic Four, Issue 1 (1961).

Also striking is how little ink is devoted to actual action sequences. For example, when the Mole Man's big green meanie from the cover of issue 1 finally makes his big appearance, the battle is devoted one single panel of the Human Torch "buzzing around the monster's head like a hornet." On the next page the Four "race for the surface." And that's it. Kirby and Lee just move on.

So, a little wordy, and the eye candy element is not so strong, but also fun and very theatrical.

-d.d.