Thursday, July 25, 2013

Drive, He Said

My first Nicolas Winding Refn film was Bronson (2008), which I hated because it treaded over the same dramatic elements too much: it was a movie about a badass who fights when cornered, so he goes to prison where... guess what?... he gets cornered and fights. In the film's defense, it looked amazing with its theatrical lighting stylization, and I had been burnt out by a festival schedule where I had already seen three films before Bronson that night.

Drive (2011, Refn) is a treat. Cliff Martinez's synthesizer 80s New Wave madness and pop songs really characterize Drive. And Carey Mulligan's damsel is the right kind of distress The Driver (Ryan Gosling) needs to check his desires. Comedy and violence finally add to create a work that can travel around to plenty of audiences effectively.

Power attracts beauty.

Only God Forgives (2013, Refn) is an urban Crime Drama that takes place in Bangkok and focuses on the few individuals who wield substantial power in the close-knit criminal underworld, and the attainability of beauty, justice, and morality that their respective statuses and power afford them.

The film opens with a kickboxing ring Julian (Gosling) runs. Slow camera dollies fluidly present sumptuous production design, highlighted by real Thailand locations, elaborate black-on-red wallpaper schemes, strong red lights, and ornate floral arrangements. This Bangkok, like Tokyo in Enter the Void (2009, Gaspar Noé), is painted in its most dark, dangerous, and aesthetically elegant form.

Once the tone is established, the following 85 minutes sludge forward charged with the behemoth Cliff Martinez score, which is unlike his recent electropop funk arrangements. Martinez's score features foreboding low strings that sound like tectonic plates must be shifting, along with bizarre atonal percussion arrangements that sometimes sound like the music from the stargate sequence of 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968, Stanley Kubrick). In the film's third act climax, Martinez finally brings out his Moog funk for a big fight though--what fun.

Chang (Vithaya Pansringarm) is the central character of the film. He rules Bangkok as a Police Chief, dishing out his own brand of justice, as he sees fit--which usually involves bloodshed. His stoicism seems contagious. The entire cast barely moves a face muscle, appendage, or even mutters a word that they don't absolutely have to. This movie is heavy. It's about a triangle of powerful people who cross each other, and the ensuing resolution.

The brothels and 12 year old Thai prostitutes are shockingly beautiful in their context here. And so is the venerable Chang's karaoke performances, with his adoring disciples (Bangkok PD) solemnly and piously granting him audience.

The blocking is very important in Only God Forgives. Audiences must pay close attention to eyelines to decipher where Julian is looking often, as cuts mismatch geographical and temporal unity. Is all of this real? Is some of it imagined? Obviously we are meant to decide ourselves, but we can assume the shots of the bloody samurai sword, for example, represent something more than your typical connect-the-dots narratives.

Only God Forgives meets the challenge of the cliché, "Go big or go home." I love the way the gargantuan metropolis Bangkok can represent the pinnacle of exotic beauty and vice, and we get to study the power dynamic through a few White expatriates primarily--it's fun to imagine that these criminals are so big that they just live off the fat of the land down there pursuing the classic safe haven for American outlaws, while running shit and living the life of luxury. And it is even more fitting that they all answer to Chang, the benevolent Chang.

I just dig Chang. Something about how formidable his presence is, always wearing that short-sleeved black shirt and slacks uniform. And Crystal (Kristen Scott Thomas) is hilariously adept at being the termagant who commands her own empire.

--Dregs

Friday, July 19, 2013

Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning is as hellaciously bad as any movie ever made

I know everybody liked Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning. I also know it's been out a while.

I loathed that movie. The reviewer linked above is good at finding things that aren't there, but "ineptly told" isn't the same thing as "dreamlike". I did see one internet comment that was like "this is like somebody remade Apocalypse Now and crossed it with Dollhouse and Total Recall and and and" and those things certainly all went into the stew, but so did a whole lot of not knowing how to tell a story. I will say that both Lundgren and Van Damme give really really really bizarre performances that I liked a lot, and some of the fights were...I dunno. Like the director and fight choreographer watched a lot of video games and wanted to recapitulate them. Here are a few claims the reviewer made.

This movie is a secret masterpiece.No.

Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning is a movie Werner Herzog, David Lynch, and Shivers-era David Cronenberg might make

The actual director, John Hyams, has a distinctive voice and style.

Yes:

He and his cinematographer, Yaron Levy, create a nightmare-scape of blighted semisuburbia through which the hero drifts

No:

The compositions are beautiful.

...

The cheapness of the setsYes.

enhancesNo.

Interiors look like Gregory Crewdson photographs and exteriors look like William Egglestons.No.

No, and then again, no:

But the movie is more than just a feast for connoisseurs of composition and atmosphere.

No:

It both invites and supports a close reading.

No:

In Day of Reckoning, the history of the individual is a alterable commodity, subject to manipulation by both the state and those who oppose it.

Yes:

At the same time, John’s search for his family’s killers folds back on itself to become an investigation into his own identity

No:

and then a radical recalibration of his moral code;

No, and then again, no:

in addition to being a political parable, the story is a subtle and elegant portrait of a consciousness maturing from psychological childhood to adulthood.

Yes:

When he realizes his memories are untrustworthy, he faces a climactic choice

No, and then again, no:

about the most fundamental of human questions

No:

Universal Soldier: Day of Reckoning is the most exceptional movie of 2012

Yes:

he made a strange,

...

haunting, sometimes even beautiful odyssey

No.

Thursday, July 18, 2013

A Grotesque Moment.

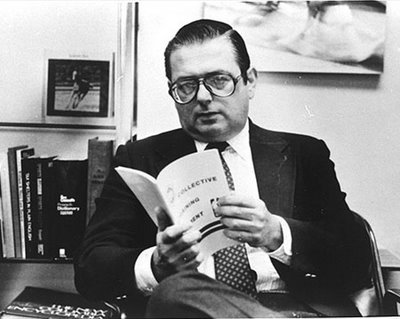

The gravitational pull exerted on me by McCann's argument also stems from the fact that I've read David Halberstam's The Breaks of the Game. Specifically, the tale of Larry Fleisher.3

The Fleisher section is where Halberstam lays out the founding of the NBA Player's Association. I have found that Halberstam's version of events appears to include episodes I have not found recorded elsewhere, or at least not on the 'nets. I suppose it's for this lack that I want to get a few of the better parts out there. In direct relation to McCann's article there's this gem.

The owner often quite unconsciously looks down on his players. In part it was a reflection of the fact that the owners thought the athletes were stupid, but it was also a feeling that they should be eternally grateful for the chance to play a little boy's game and be paid for it. With blacks, Fleisher thought, the attitude was far more blatant and nakedly expressed, the racism barely concealed; there are not thousands, but millions out on the playground who want your job, so should be even more grateful.4I consider this the root of seeing things from the owner's perspective. It's important to note the basic prejudice here is that NBA players are athletes, & athletes ("jocks") are stupid. In addition to this there is the "you're getting paid to throw a ball through a hoop" angle, which implies that players should be grateful, & do as they are told.

This second attitude turned out be the very crux upon which the nascent player's union won their first concession. It was the 1964 All-Star break & after 4 years of effort the player's union wasn't getting anywhere. The owners simply weren't listening. However, Fleisher's early strategy had been only to recruit the best players on each team. "They wanted first and foremost the peer respect worthy of a Russell or a Petit or a Wilkens, and secondly they wanted players skilled enough to be immune from front office pressure."5

In '64, NBC was bailing on NBA coverage. ABC decided to do the All-Star game, w/ the tacit understanding that if ratings were good they might pick up the '65 season. In the '60s the NFL was rolling in the cash w/ lucrative teevee contracts, & NBA owners wanted a piece of that action. This placed the players' union in a position of leverage, & they decided to strike - by not reporting to the floor for the All-Star game - demanding only a most-minimum of a pension plan. The owners said no.

The strike was a shaky business; a few minutes before game time it was still uncertain they would go through with it. The breakdown was about eleven to nine in favor and some influential players like Wilt Chamberlain wanted to play now and negotiate later. At that moment Bob Short, one of the owners of the Los Angeles Lakers, sent word down to the locker room that the two Laker All-Stars, Jerry West and Elgin Baylor, better get dressed and get out on the floor immediately or they were gone. It was a grotesque moment and it had a sobering effect on everyone in the locker room: West and Baylor were two of the most respected people in the history of the game. Yet were was an owner treating them as if they were untested rookies, do this, do that, go here, do as I say. The mood in the room swung completely, and solidified behind a strike. ABC meanwhile was squeezing the owners. If the players were not dressed and on the court in twenty minutes, ABC said, there would be no coverage this year or next year. With that the owners folded and promised a pension plan.6Bob Short's command is definitely something I've never found floating about on the 'nets, probably because Halberstam is right in identifying its ugliness. NBPA histories will occasionally mention the threatened strike of the All-Star Game, but will ignore the particulars of what went on in the locker room that day.

-d.d.

* Apologies. I found this lingering in my drafts and figured hell with it let's hit publish.

1 Link broken when Abbott went to ESPN.

2 Link broken when Abbott went to ESPN.

3 Halberstam, David. The Breaks of the Game. Ballatine Books. New York. 1981. p. 341-349.

4 ibid. p. 344.

5 ibid. p. 344-345.

6 ibid. p. 346.

Wednesday, July 17, 2013

UPS is Decadent and Depraved: A Tale of Porches (Which Do Not As Such Exist)

Initial Question: "porch"? This should have been delivered to my office, which is entirely porch-free. Where is my package?

Susan B.: Hi, this is Susan B.. I'll be happy to assist you.

Fat: Hi, great, thanks.

Susan B.: Just a moment while I look into that for you.

File attachment upload has started.

The file porch.png (72.16KB) was received.

Susan B.: I am showing the package was delivered to:

xxxx PARK BLVD

OAKLAND CA xxxxx

Is that your correct address?

Fat: Sigh.

Fat: That's an apartment building.

Fat: I am #6.

Fat: There is no porch there either, and several days ago I paid to have the address changed.

Fat: So there's kind of a lot of problems there.

Susan B.: I do see apartment 6 as well.

Fat: Okay...

Fat: So...

Susan B.: Have you looked around your delivery area possibly behind and bushes or furniture and check with any other household members that might have picked up the package?

Fat: I guess I'll leave work and go do that.

Fat: Is there a reason I was charged to change my delivery address when the delivery address was not changed?

Susan B.: I hope you are able to find the package, but if not, what you will want to do next is contact the shipper and let them know you never got the package so they can initiate a tracer investigation. Shippers are encouraged to report lost packages because receivers may not have all the shipment information needed to perform a thorough investigation.

Fat: I think I have enough information!

Fat: I changed the address, was charged money to do so, then your driver took my package to the wrong address and dumped it on a non-existent porch.

Susan B.: Sorry you were charged in error. I'd be happy to message the local center and request a refund for you. May I have your contact phone number including your area code please?

Fat: xxxxxxxxxx

Susan B.: It will take me just a few minutes to complete the message and I'll be right back with you.

Fat: Okay, thanks. While you're working on that message, can you explain why the UPS InfoNotice(R) I received said my written authorization was needed? B/c I didn't give them any written authorization to dump my package on a non-existent porch.

Susan B.: Thank you for you patience. Urgent message is on the way to the center and they'll be giving you a call within one hour regarding your package. The shipper did not send your package with a signature required at the time of delivery, so it is up to the driver's discretion whether your package is left or not.

Susan B.: Is there anything else I can help you with today?

Fat: Nope, thanks.

Monday, July 08, 2013

The 5th Film by Sofia Coppola

However, her films exhibit an anemic quality that I imagine resembles what Coppola is like in real life. From what I've heard of her public speaking persona, she often mumbles, appears fatigued, and languidly struggles to make her points (I wonder if she's always like that? Her father, Francis Ford Coppola, seems incapable of ever shutting up.).

So, as an American female filmmaker of personal and original works, she has no peers. The only other American female voice I can think of in cinema to point out currently is screenwriter Diablo Cody. These two women maintain a literary consistency to their work that is responsible, without sacrificing the quality of the entertainment.

Did anyone see the alternate design Spring Breakers (2012, Harmony Korine) poster that this ad resembles? It's no shocker that advertisers would try to piggyback onto a market trend. Yet, The Bling Ring (2013, Sofia Coppola) is an entity that's saturated with themes of imitation, impostors, and moral and intellectual wastoids. Since The Bling Ring operate as criminals who are obsessed with looking good and getting rich by assimilating with and robbing those who already are good looking and rich, they are following the newest trend this summer, as evinced by Spring Breakers or Pain and Gain (2013, Michael Bay).

There are no characters or character development. All members of the Bling Ring Five serve a single function--they steal. That's it. We're introduced to them as a gang of thieves who seek high price-tagged luxury goods, they succeed, and they are punished. The plot archs, but the characters do not. This works because it fits the world of the story. I don't want more character here because it's depicting shallow teenagers who are looking for something that they don't know themselves--fun--and don't know it 'til they find it.

This feels like Coppola's adaptation of the video game Grand Theft Auto. The bulk of the film is a pass into the proceedings for the sake of fun, as opposed to a glimpse into the procedural of why and how they did it and why and how they got caught. Go read Crime and Punishment if you really care about heftier literary crime narratives that pathologize burglary.

The familiar structure of inserting mock interview footage of the culprits after they've been convicted of their crime amidst flashbacks of the crimes themselves seems like a new direction for Coppola, but it is similar to the structure used in The Virgin Suicides (1999, Coppola).

After The Virgin Suicides, Gus Van Sant would spend the '00s churning out his "Beautiful Corpse Trilogy," Gerry (2002), Elephant (2004), and Last Days (2005). Van Sant and Coppola have a lot in common. If Van Sant's trilogy can be said to have followed The Virgin Suicides, Coppola definitely seems to have returned the homage. Coppola hired DP Harris Savides (who shot all of Van Sant's trilogy) to shoot her 2010 film Somewhere, and The Bling Ring was his final film. By itself, this is weak evidence, but the pacing of Somewhere was glacial and the point of view in general feels more detached.

Savides' look is desaturated. There are no strong blacks or whites. He doesn't light for subjects, so actors often walk through areas of the set where they fall off into shadows. And this obviously stands out against the complete opposite look of Spring Breakers.

The production design is the star of this movie. We get the cool Coppola teen girl bedrooms, although the mansions are superbly evoked. It's almost like we're back in her 18th century Versailles.

The music is every bit as legit as it should be since we're supposed to feel like we are hanging out with the coolest kids in America. The culture of singing in one's car is also an astute addition.

While I did say there was no character, I'd like to close with one final Van Sant analogy. Nicky (Emma Watson) isn't developed as a character really, but her two dimensional stereotype strongly resembles that of the Buck Henry-created sociopath Suzanne Stone (Nicole Kidman) in To Die For (1995, Van Sant). And Nicky seems to anchor the cast.

At least the actors were all actually pretty and young. Katy Chang is flawlessly cute.

While the film doesn't attain the heights of an actual tabloid opera, its modestly scaled case study does manage to show what it feels like to be a teenager again; and additionally, the dangers and excitement of breaking into houses, burglary, and snorting cocaine (for those of us who didn't actually experience these thrills first hand).

--Dregs

Saturday, July 06, 2013

The More You Look at Something the Less You See

To separate movies from films, the Coen Brothers' widely praised works are typically their movies: Raising Arizona (1987), Fargo (1996), The Big Lebowski (1998), O Brother, Where Art Thou? (2000), No Country for Old Men (2007) and True Grit (2010); and unfortunately, it's been a long time since I've had the desire to revisit these in hopes of finding something new.

However, their films: Barton Fink (1991), The Man Who Wasn't There (2001), and A Serious Man (2009) easily remain some of the most intellectually stimulating and classically entertaining narratives any American filmmakers have crafted since the 1990s, in the modern era. Yet, their movies are necessary to identify them as auteurs, and their films only become stronger if you take their body of work as a whole.

Yesterday The Man Who Wasn't There screened in a 35mm print at a theatre. Since this movie was shot on 35mm and converted to a DI, watching it on DVD or digitally projected in a theatre leaves something to be desired. However, seeing the film projected in 35mm returns the black and white converted DI to its native analog look because the print shows dirt, dust and other debris and feels like you're watching an old black and white movie from the 40s.

The black and white look and the film's period small town somewhere near Sacramento, CA setting make this a Film Noir. Normally I confine Noirs between 1941-1958, but this 2001 movie qualifies because they set their film back then. But this isn't merely a Film Noir. It's more like the Coen Brothers making a Neo Noir because they are drawing heavily from the established conventions of historical Film Noirs, but have crafted the film as an existential crisis--with a plethora of big questions, most notably: "What kind of a man are you?" And in addition to all of this, they have succeeded in delivering one of their most sparkling deadpan comedies, with one of their most uniquely droll and prosaic assortment of everyday small town folk, dryly skewering all things ordinary.

The look of this film separates it from B-movie Noirs. Roger Deakins primarily using the barbershop, photographs sublimely contrasty, detail cluttered set pieces almost as gorgeous as images Henri Alekan achieved in Der Himmel über Berlin (1987, Wim Wenders). Also, the Nerdlinger's department store features cavernous shadows and broad pillars of blackness against smoky shafts of light that create geometrically designed representations of the protagonist's psychological inner chaos like the films John Alton shot in the late '40s. And notice the striking use of medium to medium close up-framed dolly tracking shots, overcranked, and often rain soaked; these are among the most lyrical segues in the film.

Some of the strongest evidence to support categorizing this film as a Film Noir is Ed Crane's guarded near-paranoia. He's cynical, as are most hard-boiled Noir protagonists. And he's our narrator, so in a way, the film is cynical. Film Noir often means an American looks around sometime after The War and realizes people, society, or the government aren't what they seem. This is Ed Crane's path. Sizing people up seems to be his only reason for living. And he usually concludes that they're all phonies. Think about how often he slings that slur.

Birdy almost takes on an existential significance, as she's obviously something like a manifestation of Crane's ideal female. And in the glorious scene where she attempts to give him fellatio as a consolation prize, Crane's dreams are finally shattered once and for all, causing him to take account of his place in the universe one last time.

Existential is a big label that gets thrown around way to much. I'm not saying I'm the one to categorize this film as such, but I think it does ask big questions instead of setting the same conflicts and resolutions as most plot-driven works. There is something said without words that floored me when Crane gets his leg shaved before his execution--because we remember that everynight he used to shave his wife's legs in the bathtub--like, how odd that on his last night alive someone else would be shaving his. There's no point. It's a mere observation. But, what else is there? These shots may support the motif that Doris' marriage proposal suggests ("Why? Does it get better?").

She has a point.

Maybe this is all there is.

Doris (Frances McDormand) is a riot as the comedic relief, and Crane is here merely to serve as her foil mostly. She's got the balls and spits fire like one of Hawks's gals. And what cracks me up is that religion or a higher power isn't a governing factor for Ed or Doris (or anyone else in this movie really) but, she kind of symbolizes everything the ten commandments try to dissuade. Doris cusses like a sailor, loves to use blasphemy, "Enjoy your goddamn cherries," is racist, "I hate wops," is an alcoholic, commits adultery, commits grand larceny against he employer, and finally is convicted of murder. The irony is that even though Doris didn't kill Big Ed, one wonders how long before she might have.

Her first line in the film is a riot, "Bingo!" I saw McDormand on a Charlie Rose interview from the time of the film's release and I remember she said some of the best direction she had was in that scene because Ethan told her, "when she gets bingo, it's life or death for her."

The casting in this film is brilliant. No one holds a candle to Tony Shaloub (as Freddy Riedenschneider). Riedenschnieider's machine-gun rapid-fire dialogue as a fast talking big money attorney from Sacramento takes the second half of this film into vastly entertaining dimensions. Everyone is a small town rube, but he kicks the cobwebs off of the mausoleum once he arrives. He talks fast, eats fast (and voraciously), and thinks fast. He's arrogant, rude, manipulative, and driven. His musings on Heisenberg's uncertainty principle are ridiculously hilarious. Although my favorite Riedenscheider lines have always been his curt summary of how crummy Doris' case looks:

In closing, the haircuts for kids were:

The Butch

The Heine

The Flattop

The Ivy

The Junior Contour

(And occasionally) The Executive Contour

Friday, July 05, 2013

Watch This and Grab the World by the Asshole

I hesitated watching the movie because Blu-ray and a city that shows and cares about movies makes it hard for me to watch low-res shoddy transfers, if I can help it (often I can't, i.e. Warhol's films). Thanks to the Alamo Drafthouse there was a screening of The Candy Tangerine Man (1975, Matt Cimber) projected in 35mm.

Style is what this movie has going for it.

The genre is

I haven't done adequate critical work to call myself knowledgeable about Blaxploitation movies. I grew up watching Dolemite, but that's about it. I do like a movie called Emma Mae (1976, Jamaa Fanaka) that I saw fairly recently. That was some of the best Blaxploitation because of the way that it used real locations and non-professionally trained actors to evoke a vérité Compton.

But The Candy Tangerine Man doesn't transcend any of its low budget limitations in any significant way. Style does go a long way though. The star of the film is John Daniels, who plays The Baron. The Baron is a pimp, but in this film he's glorified and heroic.

Something about the score really stood out. It's so slow. It creates a constant sense of foreboding because of its menacing slow nature, but this also compliments The Baron--he's slow and menacing. The Baron is an anomaly in this film because every other character whines in obnoxious high registers except him. And everyone else are two-dimensional stereotypes but him.

This milieu is so rich. The Candy Tangerine Man doesn't come anywhere near having the verisimilitude of Iceberg Slim's masterpiece 1967 novel "Mama Black Widow," but it does cover the same turf (procuring and prostituting as run by Black people in a metropolitan US city). There is a scene where a rival pimp challenges The Baron: "I ain't into the slave trade," which seems like a pretty hefty accusation, but The Baron (and the movie) let this comment slide.

The big twist in this movie is that The Baron has a beautiful wife, child and home in the suburbs that he visits by day, and who are unaware of his alter ego's profession. So if one were to look at the morals (I'm not gonna dare attempt to say racial politics) this movie upholds, it is clear that it sees the pimp as industrious and prestigious rather than exploitative or immoral. And why not? I like seeing movies from alternate viewpoints, and the rare movies where crime does pay are always fun.

--Dregs

Wednesday, July 03, 2013

Hideous Mutant Freekz

One of my earliest childhood memories was visiting a house where I remember playing with Lite-Brites and being astounded at something on TV that an older boy was watching. All I recall is seeing the dude who played Bill S. Preston Esq. (Winter) being chased through a set that resembled The Evil Dead (1981, Sam Raimi) with the Ram-A-Cam by a bald woman, while Bill yells, "Oh no, it's Sinéad!"

"The Idiot Box" was my introduction to television sketch comedy programs and I've been keeping up ever since. "Portlandia" is a lot more like "The Idiot Box" than it is "Monty Python's Flying Circus," "Saturday Night Live," or "The Kids In the Hall."

And then there's the tale of one of the rare instances in Hollywood History when someone slips something past a major studio, gets a ton of money, makes something the studio ends up disowning, but because the film survives on home video and repertory screenings, becomes a cult classic. The way the story goes basically is that after the success of Bill & Ted, Alex Winter pitched a similar vehicle to star he and (a disguised in dog makeup) Keanu Reeves to Twentieth and they gave him fifteen million dollars before they realized they hated his film, Hideous Mutant Freekz.

Have you ever found the style of a filmmaker so brilliant and enjoyable that you wish you could see other work they've done in the same vein? Jackpot!

The plot is that Elijah C. Skuggs (Randy Quaid) illegally purchases a toxin called Zygrot 24, which has hideous freak side effects, and shanghais a band of victims to perform in his sideshow, Freek Land.

This is "The Idiot Box" the movie, for sure. Fans will get all of the trademark ADR cheesiness, interchangeable absurdist roulette structure that gives "Family Guy" a decent run for its money, Alex Winter, and stupid gross humor; and Freaked opens with a VO PSA that it's safe to return to your homes because the "Flying Gimp," has been killed.

I've had a few memories of watching a movie for the first time in the theatre and being shocked at the consistency of the amount of times I'd laugh. Usually upon revisiting the films, I could not recreate the alchemy. I think for me it was BASEketball (1998, David Zucker) first--I'd learn that ZAZ did this as early as The Kentucky Fried Movie (1977, John Landis); then there wasn't really anything similar until "Family Guy." Yeah, when I first saw "Family Guy" I was enthralled because I felt like I was laughing every 30 seconds non-stop, every episode for the first season.

Anyway, I haven't been able to watch "Family Guy" since the previous millennium. But Freaked was as good as I'd always remembered.

The big budget shows. The production design, sets, costumes, and especially the prosthetic special effects are dynamite. Alex Winter as Ricky Coogin spearheads the adept comedic ensemble in the raucous, rowdy, raunchy, ribald, rotting putrid gem of a freak show.

I love Stuey Gluck (Alex Zuckerman) in all of his overly-sentimentalized, Steinbeck meets The Champ adorned goofball screen appearances.

The sound design is as aggresively Hollywood as Jablonsky doing Transformers. And this production comes off seamlessly because the creators actually worked for 2 years on development before the cameras were brought in for production. They left nothing to chance, which is very impressive for a first-time director.

Some of the pop culture references might be lost on some (like the "Jake and the Fatman" diss.) But most of the gags are, what Winter describes as, "dumb jokes that only guys get." I laughed the hardest I have in a long time at the scene where they reveal flashbacks for every freak to show how they were shanghaied by Skuggs. The last flashback tilts down to a hammer on the ground. Next, intense suspensful music, sound effects, lighting and editing reveal through flashback that once upon a time Skuggs bought this character as a wrench in a hardware store.

Aesthetically this movie is important because I love all things toxic, pop culture, and absurdist black comedy. And I really can't express how important this film is to me, being one of the trashiest oddities I actually hold as high art.

--Dregs